Essay on Deinstitutionalization of Mental Health Patient

FOR STUDENTS

Creating alternative facilities to reduce mental illnesses

Deinstitutionalization is the replacement of psychiatric facilities with community-based interventions to care for people with mental illness as a way of reducing their sole dependence on mental institutions. It was initiated with the aim of reducing the burden of mental health institutions by creating alternative facilities in the community.

Although in some special circumstances mental health institutions and facilities require a longer stay of patients, deinstitutionalization encompasses community support for people with mental illness during this period.

This is perhaps as a result of the increased number of people with mental health issues and over congestion of mental facilities. However, deinstitutionalization has fallen short of the reasons behind its establishment and has complicated the process of readjusting people with mental health illnesses. This article discusses the historical background of deinstitutionalization, the current perspective, and the negative impacts of deinstitutionalization on society and those with mental health challenges.

Historical Background of Deinstitutionalization

Institutionalizing of mentally challenged people reached its climax in the 1960s when the anti-psychiatric movement began to seek alternative means of caring for all those with mental health issues. The search for a new alternative to mental health care began as a result of the observation that most mental health patients were kept in hospitals and facilities that increased their isolation from the community which made reintegration and coping difficult when released after recovering from their illness. Prior to this time, it was believed that if mental health patients were institutionalized early enough about 70% of them will recover. This assumption turned out to be false, although some did recover, the success rate fell below the assumed figure. Improvements in health institutions, living conditions in America’s asylums, and the incorporation of new treatment methods no longer made any significant improvement to mental health; in fact, it seems to increase the burden of the illness. At the same time, the number of institutionalized people with mental illness increased.

More so, the natural reaction to curtailing the aforementioned issue of overcrowding of health institutions was building more institutions. Building more institutions climaxed in the 1980s as a result of the unsustainability of the project because it was capital intensive and counterproductive. Subsequently, the cost of caring for mentally sick people became very high and a lot of people were deprived of comprehensive mental health care. This situation also necessitated the medical community to seek new means of caring for people with mental illness. It was through this quest that most of what is known as the deinstitutionalization was discovered.

The answer came from a very small town in Belgium with the tradition of caring for mentally challenged people in their homes. However, the origin of the practice of caring for mentally ill people in this Belgium town is full of tales and legend that is hard to verify its authenticity. But it is well established that the practice has a strong religious undertone, as there are records showing that people with mental illness were kept in the church for nine days cleansing rituals. As news about the efficacy of the exorcism program of the church spread, accommodate the people needing a cure who came from near and far became a challenge. The church, therefore, asked the residents (its adherents) of this Belgian community (Gheel) to accommodate patients waiting for a cure from the church. Thus began the tradition of boarding those with mental in the area.

Accommodating people with mental illness in private homes continued as a ‘church initiated program’ for a long time until 1852 when the State took over the administration of the practice. It was during this period that the practice received more medical reforms, such as how mental patients are to be treated and supervised as members of the community. At this point not only those seeking a cure for mental illness were attracted to Gheel, but also the members of the medical and scientific community, who were amazed as to how those with mental illness could live freely and peacefully with the general public without any hindrance or restraint. This observation was particularly impressive because it was difficult for institutionalized people with mental illness to be released to the public, even at the request of their family members as a result of the popularly held belief of the destructive nature of the mentally ill persons at that time. Even in such confinement, mentally ill people were abused and unnecessarily restrained for fear of letting them express erratic behavior.

However, it was not until 1879 that the United States stopped the use of mechanical restraint in all public institutions for the insane after it discovered the prevalence of its use in almost all mental institutions. Eventually, a psychiatrist came to the conclusion that mechanical restraint was unnecessary and that minimum force was the goal while dealing with people with mental illness, even though it did not state what ‘minimum force is’. In addition to this, hospitals no longer provided the services required for rehabilitating those with mental illness such as vocational training, medication, and therapy. This was especially true when people realized the profit that could be made if certain aspects of mental health provisions are monetized rather than sourced internally in times past. This further created idleness in the care system for patients, as most of the activities normally organized by the institution became necessary.

Several legal battles also characterized the use of re-admittance to mental institutions or full discharge from the centers. In 1975 the Supreme Courts in one of its ruling declared that except a person poses as a danger to himself or to others they should not be confined to a mental health institution. In another ruling in 1999 mental illness was referred to as a disability, which is covered under the Americans with Disability Act. Therefore, all government agencies were required to provide mental health based treatment in community-based institutions rather than being placed into permanent mental health institutions, otherwise known as deinstitutionalization.

Current Perspective of Deinstitutionalization

Today, the current state of deinstitutionalization takes a different dimension from its original concept as mentioned above. According to modern concepts deinstitutionalization, three criteria are essential for establishing a good deinstitutionalization program. They include discharging admitted mentally ill persons to an alternative community facility, redirecting new mental patients to alternative facilities in the community, and designing a special care service for mentally sick people not requiring confinement in a mental institution. All these are to ensure that people with mental illness are treated as open as possible and also reduce the possibility of confinement to only those who absolutely need it.

The ideation of deinstitutionalization suggests that people will do better in community facilities than in mental institutions. An assumption that the community will be less aggressive to mental patients than mental hospitals; as such deinstitutionalization becomes therapeutic to people with mental health challenges, and finally this project will be cost-effective and time-efficient for the government and health care providers. All these hypotheses were not critically tested before the program began. Therefore, at its early stages deinstitutionalization became as though it was just a game of reducing numbers of those in confinement than of the wellbeing of the mentally ill persons.

However, the current deinstitutionalization program has helped reduce the number of institutionalized patients to the barest minimum and ensures that adequate care is given to mentally ill people in the community as opposed to mental health institutions. For instance, in the mid-1950s there were over 500,000 institutionalized people in the United States alone with a total population of just over 165 million. If that is contrasted with the number of institutionalized mentally ill persons in just forty years after the program began, the number has dropped significantly to barely over 57,000 patients of a population of about 270 million people. This has led to the closure of many mental health institutions and a reduction in the number of beds allocated to mentally ill individuals in those hospitals that are still opened for mental health care.

Nonetheless, most mentally challenged people enrolled in the deinstitutionalization program are better adjusted with community life when compared to those in mental institutions. In areas where all three aspects of deinstitutionalization have been fully implemented, people who suffer from mental illness have reported improved quality of life. Such reported improvements include the ability to hold down full-time employment and care for themselves. These effects are rare with institutionalized patients.

However, the aforementioned benefits are just an oversimplification of the effects of deinstitutionalization. There has been a twist to the issue of mental deinstitutionalization even in areas where people have access to adequate funding. Most of these negative correlations were as a result of the unforeseen circumstances of deinstitutionalization.

Negative Impacts of Deinstitutionalization

With all the positive effects of deinstitutionalization, it has brought a lot of negative impact on the mentally ill persons and the community they reside in. The negative impacts as discussed by several kinds of literature include the following:

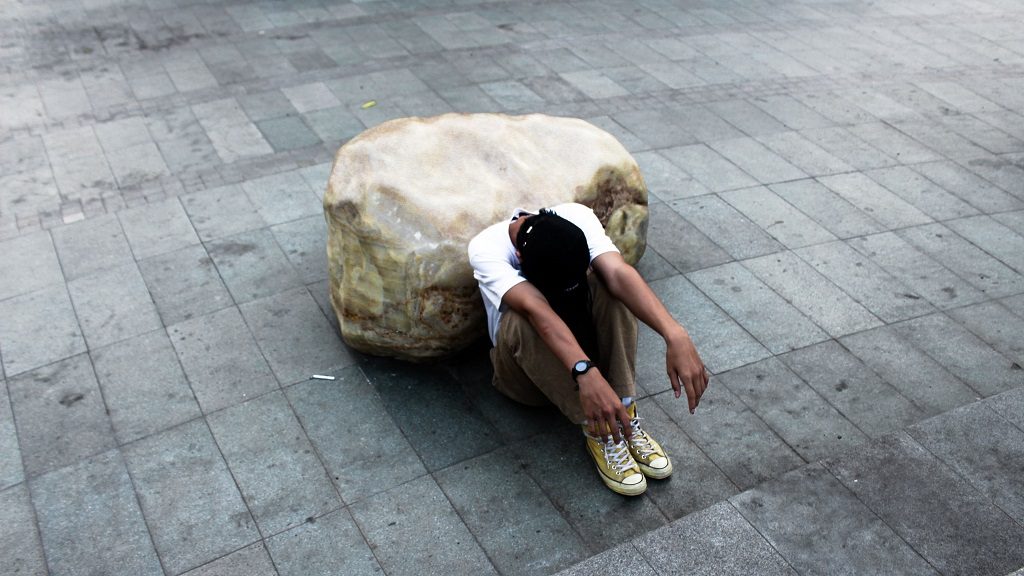

Inability to Care for a New Set of Severely Mentally Ill Persons. Since the implementation of deinstitutionalization, there has been a rise of a new set of mentally ill people who do not belong to the above-mentioned group (institutionalized mentally challenged people) that has not been planned for in the deinstitutionalization policies. An example of this new set are homeless people with very severe mental illnesses like schizophrenia or people with psychotic depression and have never been institutionalized in their life.

To get a better understanding of why this new generation of mentally ill people who have never been institutionalized is problematic, it is important to note that people who were previously institutionalized have been conditioned to obey orders and follow instructions to the point that they are able to accept and continue treatment a habit that continues when they live freely in the community. While those who have never been in the institution or spent prolonged hours in a mental institution poses a huge challenge to getting treatment and rehab, such as refusal to take prescribed medication. Such habits could make it difficult to treat mental illness

Uncontrolled Community Settings and Substance Abuse due to Deinstitutionalization

Unmistakably, mental illness has transformed, as much as almost any other illness because of the daily psychological, emotional, and physical assaults people face daily. In times past people who become mentally sick are institutionalized, as such restricting their access to hard drugs and alcohol. This new generation of the community-based mentally challenged group is often exposed to harmful drugs on the street that might temporarily reduce mental illness symptoms but ultimately complicate health.

Also, the fragmentation of mental health service and private housing required by deinstitutionalization arrangement for most mentally challenged persons is a barrier to recovering from mental illness. This is because individuals with a mental health challenge might be a long way from carrying such heavy responsibilities. Although the aim of deinstitutionalization is to allow the challenged person integrate and know how to use different facilities in the neighborhood, the community might not be so open and willing to help out in providing necessary assistance for these persons, when it is needed. This problem has been seriously overlooked when deinstitutionalization was conceived.

Another major challenge is that most people with long-standing mental issues might find it hard to even hold down accommodation because they are ill-equipped to manage simple disagreements, such as tenant and landlord misunderstanding. If close follows up is not issued early enough on those with mental illness, most might become confused and sometimes wander away from home and school perhaps to get away from the pressure that comes from community living.

In addition, many people with mental health disabilities have been involved in activities that have affected not only their health but also the wellbeing of free-living citizens. Most crimes committed are as a result of mental illness, as such the justice system is often faced with a huge dilemma of incarceration in mental institutions or sending culprits to prison. A lot of the above-mentioned problems could have been prevented by the institutionalization of mentally sick people.

Recommendations

It will be very unfair to say that deinstitutionalization is a total failure because it has provided many mentally challenged individuals to live a seemingly normal life possible. However, a few adjustments can be made. One of which is tailoring mental health community service to individuals rather as a group; this will involve a pre-mental test and assessment on individuals with mental issues to ascertain if they can cope with stress and unpredictable environment before they are allowed into the community programs. Another adjustment to deinstitutionalization should be continuous planning of health care service; this will involve a regular reassessment of the needs of the person involved based on long and short term goals, in order to fully meet the needs of the mentally challenged person. This is a result of the ever-changing need of the individual.

Conclusion

Deinstitutionalization is basically replacing psychiatric facilities with community-based intervention to care for people with mental illness and reduce sole dependence on mental institutions. This concept started from the Belgian community of Gheel that accommodated patients waiting for a cure from the church but could not secure a space. People from all over the world were thrilled as to how many mentally challenged persons were allowed to live normal lives in the community unrestrained. Since its incorporation into the system of mental health care, it has helped many mentally challenged people live normal lives and become gainfully employed. But it is still a far cry from its expected outcome. As such it is recommended that several adjustments such as tailoring mental health community service to individuals with mental illness and also involve regular reassessments of the needs of these individuals to fully meet the standard possible of deinstitutionalization.